Navigation: Hankeys of Churton > John Hankey > Robert Hankey > Robert Hanky > Thomas Hankey > Henry Hankey > Thomas Hankey >

1740-1793

Chronological Summary

1740 Born [Clapham]; baptised City

1765 Partner of Hankey & Co.

1770 His father, Sir Thomas Hankey, died

1771 Son William Alers born, London (where?)

1773 Known to be at Southborough, Bromley, Kent

1773 Head partner of Hankey & Co.

1774 Dau. Charlotte Weaver/Hankey born, baptised Westminster

1776 Dau. Sarah Hankey born, baptised Bromley

1779 Dau. Louisa Hankey born, baptised Bromley

1781 Married Elizabeth Weaver, St Martin in the Fields

1784 Son John Barnard Hankey born at [Fenchurch St] baptised City

1784 Inherited the estate of John Barnard, his uncle

1786 Dau. Elizabeth Hankey born, baptised City

1786 Known to be still at Southborough, Bromley

1786 Bought lease of 18 Bedford Square

1788 Son William Alers at Edinburgh University

1789 Purchased Fetcham Park

1791 Son Thomas Hankey born at Fetcham

Eldest surviving son of Sir Thomas Hankey and Sarah nee Barnard. Thomas was born on 30 Jun 1740, possibly at his father’s house at Clapham, and was baptised on 21 Jul at St Dionis Backchurch. Of ‘very good sense & good education’, he probably received his schooling from tutors.

After the death of Sir Henry Hankey in 1737, Sir Joseph Hankey became head partner of the family banking firm of Hankey & Co. of 5, 6 and 7 Fenchurch Street, and ran it very successfully, together with his younger brother Sir Thomas Hankey.

By the early 1760s they must have been concerned to ensure their succession and admitted to partnership their respective sons, Joseph Chaplin Hankey in or about 1763 and Thomas Hankey in 1765, together with Stephen Hall (one of only two outsiders known to be a partner, and who remained such until his death in 1809, aged 82).

Sir Joseph died in 1769 and Sir Thomas in 1770, when Joseph Chaplin Hankey became head partner. But Joseph Chaplin Hankey shot himself in October 1773, leaving Thomas unexpectedly to assume the responsibilities of head partner, a position he held for the next twenty years.

On his father’s death on 13 July 1770, Thomas was already thirty and unmarried, but freed of parental control he soon fathered a son, William Alers (later Alers Hankey) who was born to Miss Maria Alers on 15 Aug 1771. It is almost certain that Thomas Hankey and Miss Alers were never married; indeed William’s son John Alers Hankey offered a large reward for the discovery of a marriage certificate, without success.

Three daughters followed before Thomas’s marriage to Elizabeth Weaver in 1781:

- Charlotte (1774-1816), born on 25 Jan 1774, possibly at Westminster. She was baptised on 23 Feb 1774 at St Martin in the Fields as ‘Charlotte Weaver, daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth’; the 1773 rate book for St Martin in the Fields shows the name Weaver at Mercer’s Street. Charlotte, by then Hankey, was married on 7 Jul 1796 at Fetcham to her first cousin Frederick (later Lt-Col Sir Frederick) Hankey (1774-1855), third son of the late John Hankey of Mincing Lane. An ‘accomplished & elegant girl’, ‘she had good qualities, very sensible, but loved preeminence’. Charlotte died on 25 Sep 1816 at Worthing; she was buried on 10 Oct at St Dionis Backchurch and reinterred at Kensal Green Cemetery in July 1878.

- Sarah Hankey (1775-1857), baptised at Bromley, Kent on 8 Apr 1776 when the entry in the register was ‘daughter of Thomas Hankey, banker in London & reside at Southbarrow’ (duplicate entry ‘daughter of Thomas Hankey of Southbarrow Esq.’ in the adjacent parish of Hayes). In character, Sarah ‘was much more reserved & never took a prominent part in any conversation’. She was married on 14 May 1796 at London to Sir Hugh Dillon Massy Bt., of Doonass, co. Clare. They had one daughter, who married Felix Vaughan Smith and who died in 1842 at Fitzwilliam Square, Dublin. Lady Massy died on 28 May 1857 at Portugal Street, Grosvenor Square.

- Louisa Hankey (1778-1851), baptised at Bromley on 24 Jan 1779 (with similar entries in the registers of both Bromley and Hayes). Louisa was married on 3 Dec 1803 at Fetcham to Matthew Chitty Darby-Griffith (1772-1823), later Major-General, of Padworth, by whom she had issue. She ‘was always a very unassuming person both as maid and wife, a dear amiable creature willing to give way to every Lady’. Louisa died on 9 Feb 1851 and was buried at St Dionis Backchurch.

Matthew Chitty was the second son of Vice Admiral George Darby of Newtown House, Hampshire and his wife, Mary daughter of Sir William St. Quintin, bart. His maternal aunt was Mrs. Catherine Griffith, the wife of Christopher Griffith Esq., from whom he inherited the Padworth estate in September 1801. In accordance with her will, he also took the additional name of Griffith.

He had a distinguished military career, serving in the Regiment of the First or Grenadier Guards for a period of thirty years. He took part in the expedition to Holland, under Sir Ralph Abercrombie, in 1799 and, afterwards, under the Duke of York, in a campaign which was an episode in the long Continental War carried on by England against Napoleon.

In 1809, Darby-Griffith was present, and lost his leg, at the Battle of Corunna in Spain, where Sir John Moore, having accomplished a retreat under immense difficulties, finally held in check the pursuing French army long enough to enable his own troops to embark. Though Sir John was killed at the moment when a decisive victory was just within his grasp.

Major-General Darby-Griffith died at Padworth House on 7th August 1823, leaving, by his wife, Lousia 3rd daughter of Thomas Hankey esq. of Fetcham Park, Surrey, three sons and one daughter: Christopher who inherited Padworth and was Member of Parliament for Devizes and married Arabella Colston of Roundway Park; Henry, who commanded the Scots Greys in the Crimea and also died a Major-General; George who became a Major in the army and died in 1846; and Isabella who married Captain Knox, RN, and died 1892.

Edited from Mary Sharp's 'A Record of the Parish of Padworth' (1911)

At the age of 41, Thomas eventually decided to marry Elizabeth Weaver (1751-1829). It was she who obtained the marriage licence, and they were married on 10 Nov 1781 at St Martin in the Fields (she of that parish and he of Bromley, Kent).

Tom Hankey’s brother John often used to recall how, while sitting in his office in Mincing Lane, a band of ringers came to ask for money for ringing so merrily at his wedding, insisting always that Mr Hankey of the City was married that morning. Knowing nothing of any Hankey wedding, John thought it a plan to extort money and that, seeing him very busy, the men were more importunate, hoping that, to get rid of them, he would give them something. The marriage was not known to the family until a year or two later, when Tom Hankey sent a message to his brother Robert’s wife that ‘he had been some time married ... and would esteem it a favour if [she] would acknowledge & receive her & use her influence with the family to do the same’; Tom’s sister Lady Hotham and his aunt Mrs Temple were among those informed, and as a result dinners were given upon the occasion all round the family. According to Tom Hankey’s niece Matilda, the young Hankeys ‘had plenty of sport in watching the newly introduced couple, & I must say Uncle Tom (who was the drollest man you can imagine) helped we young ones not a little by tutoring his poor wife and trying to make her a lady. Give the dear woman her due, she was an apt scholar & I believe died with the respect & esteem of all the young Fry’.

It is said that Elizabeth Weaver was born on 11 Aug 1745 at St Martin in the Fields, the daughter of Samuel Weaver and Sarah. Samuel Weaver was a wine merchant with interests in Portugal, and his firm was incorporated into Dow & Co after his death. Other accounts suggest that Elizabeth was of an old Cheshire family, and that she was Tom’s cook.

Tom and Elizabeth subsequently had two sons and a fourth daughter:

John Barnard (Barnard) |

1784-1868 |

(see below) |

Elizabeth (Eliza) |

1786-1850 |

Of 28 Connaught Square; died at Rome |

Thomas (Tom) |

1791-1879 |

(see below) |

Thomas’s will refers to his son John, his second son Thomas and his four daughters (three of whom were born before their father’s marriage); the will also acknowledges William Alers as his son, but his inheritance of £6000, although large, is considerably less than the other childrens’. This confirms that only William was the child of Miss Alers. Of the four children born before Thomas’s marriage, William took his mother’s name of Alers, probably because he was brought up by her, while Charlotte (although Weaver at the time of her baptism), Sarah and Louisa bore the surname Hankey. Why, though, did Thomas wait over eight years before marrying the Hankey daughters’ mother, and even then keep the event hidden for a year or two from the Hankey family?

Thomas had a country house at Southborough, Bromley (formerly the property of Governor Cameron, who often entertained King George III there). Here one of his friends was George Norman, whose son George Warde Norman left the following account of shooting in the district:

‘During my Father’s early days’ (he was born in 1756) ‘there were a few partridges, hares and rabbits, but far fewer than now. More woodcock and snipe on the Common and a very few pheasants. The dogs employed were pointers and very wild spaniels. Beagles also I suppose. Preservation of game in the modern sense did not exist. Gamekeepers were kept to kill game for the table, and these of course drove off or captured poachers if they met them. For regular shooters, the whole country was in a manner open. Thus my father and Mr Hankey, of whom the former had a little land and the latter none, went pretty much where they pleased....’

Thomas’s lands at Southborough cannot have been that small, as the Bromley parish register notes that he had a bailiff in 1773 and mentions a gardener in 1783 and 1786.

In July 1784 Thomas Hankey personally subscribed £180,000 (15% paid) to a loan raised by the Bank of England, and his firm a further £350,000.

Thomas’s already sound finances were transformed when on 24 November 1784 his uncle John (Jacky) Barnard, a noted art connoisseur and collector, died at his house in Berkeley Square. Later the same day Thomas went to the house, with his cousin 2nd Viscount Palmerston., to look for the will. They went again the next day to hear the will, which Thomas as sole executor was able to prove on 26 November, five days before the funeral. Thomas inherited most of the estate, said by The Gentleman’s Magazine to be ‘worth two hundred thousand pounds’. This inheritance included John Barnard’s important collection of prints (sold at Greenwoods in 1787), drawings (sold at Phillips in 1798), and pictures (sold at Christie’s on 7-8 June 1799 as instructed in Thomas’s will).

Thomas generously met two claims against his uncle’s estate, neither provided for by the will. On each of John Barnard’s aged servants he settled an annuity for life; and to John Barnard’s two grandchildren, whose mother had been disinherited for running away with her music teacher, Thomas paid a small ‘bequest’.

‘Mr Hankey, Fenchurch Street’ sat for Sir Joshua Reynolds on 12 Apr 1786. Apart from this entry in Reynolds’ diary, there is no other record of the portrait; but a portrait of Thomas Hankey was said to have been at Fetcham Park.

In 1786 Thomas moved into a substantial new town house at 18 Bedford Square, probably near to his father’s old house. The house still stands, forming the eastern half of the central feature on the north side of the square; until 1893 the square was sealed off by gates and tradesmen were required to deliver goods in person.

Thomas’s widow Elizabeth was left a life interest in the house, which was her home at the time of her death 35 years later.

The Hankeys and the Palmerstons

The second Viscount Palmerston (1739-1802) had dined with his uncle Sir Thomas Hankey in 1765, and remained close to his first cousins Thomas, John and Robert Hankey. His diary records numerous dinner parties, various social outings and two concerts with the Hankeys over the years, but although this is often referring to John Hankey and his wife (who came at least twice to stay at Broadlands, and had him to dine with them at Streatham and at Mincing Lane), he probably also dined with Tom Hankey, who in 1788 was a godfather to his second son William.

Viscount Palmerston was an important customer of Hankey’s Bank, but in 1789 he took serious offence against the bank on hearing that they had demanded repayment of a comparatively small loan to William Godschall, who was both his uncle and the husband of his mother’s first cousin Sarah Godschall. Trouble was already brewing when on 10 April 1789 Viscount Palmerston wrote to his wife ‘Monday dined at Mr Hankey’s, very stupid and vulgar’.. Mr Hankey’s concert was crowded with odd people as you may guess but there was some very good music.’ Three days later, from Bath, he wrote to his wife again ‘There are a few brutes in the world [as] is most certain ‘ and by the way not a more complete one in any part of it than your cousin Tom Hankey who if I had influence enough should never again be noticed by you in any way for his cruel conduct to poor Mr G[odschall]. Can one form an idea of a man of his immense affluence putting a writ into a sheriff’s hand against a relation, a man of poor Mr G’s age and infirmities, weighed down by sickness and distress to say nothing of his natural benevolence of manners which one should think would soften the hardest nature to favour rather than persecute him. To conceive that under such circumstances there can be found a wretch mean enough, who is in the possession (as he says) of £10,000 a year, to wish to distress in so public a way any man for so trifling a sum as £150 (nay I believe it’s much less) is far beyond my idea of the feelings even of the most avaricious. But I am clear in my opinion that such a being is unfit for the society of any gentleman and much less of those who stand connected by family ties with the object who is suffering from his mercenary brutality.’

There was more difficulty with Hankey & Co after Thomas Hankey’s death, as described in Portrait of a Whig Peer by Brian Connell, 1957: ‘During the years 1797-9 Palmerston was weighed down by a load of debt, which by the middle of 1798 exceeded £30,000. To ease the pressure and meet the pressing demands of his bankers he was obliged, in due course, to sell two of his English estates and to take out a mortgage ‘ on Broadlands ‘’

On April 7 [1797] he received ‘On mortgage of the Hampshire estate £10,000’, and of that sum: ‘£6,000 was paid to Drummonds, the bankers, to discharge a loan and £2,000 to Hankeys, the bankers, to reduce an overdraft.’ ‘A fortnight later further trouble was impending: ‘I owe the Hankeys more than I ought ‘ Selling stock to any amount at this time is such a loss of income as is quite serious, and yet must be done if no other means can be found.’

On April 3, 1799, he was obliged to sell another of his English estates ‘ to Henry Thornton, of the Bank of England, who paid him £11,000. The settlement of this business and the payment of the proceeds to Hankeys must have taken some time, as on October 3, 1799, we find Palmerston writing to his wife: ‘I have been this morning to meet Mr Thornton and our business will be finished directly. A circumstance has occurred with the Hankeys which will very likely occasion and I think fully justify my leaving their house. I have been indebted to them some time past £17,000 [about £3 million in today’s money], for which I paid them interest. The sale of an estate in Northamptonshire to Mr Thornton was to pay them the produce of it, viz. £11,000, leaving £6,000, which I thought and they seemed to agree, was doing handsomely by them, and that what was left unpaid was no more than what a customer like me might reasonably expect as an accommodation for a longer time. But to my surprise the next day I received a letter from the house at large, calling on me to pay in the whole and advising me to sell stocks for the purpose which I do not propose to do. This I think a shabby proceeding, but as they have a right to be paid they cannot be surprised if I transfer my business to houses that will be obliged to me for it and ready to furnish me with such an accommodation. I shall be most happy to have a fair ground of getting rid of the Hankeys, whose situation is an almost intolerable inconvenience to me, who never go into the City’.

October 4th. ‘I have settled my business with the Hankeys upon a fair compromise that I pay them something more than I intended and they are not to call for the remainder unless they particularly want it and if they do, they are not to take it ill if I go to some other house who would willingly furnish it.’

In 1839 Tom’s cousin Matilda Hartsinck (daughter of Robert Hankey) recorded her reminiscences of the life of the young Hankeys around the turn of the century:

‘The two brothers John & Robert used to laugh and quiz too & the great fun used to be to tell John Hankey’s three sons that there was a cousin for each of them. Jack the eldest had at that time rather a preference for me & he was very sore about it. Fred however could laugh heartily & help forward the joke, little thinking he was to take the eldest Miss Hankey himself, who at that time was not thought the most elegant of them, & the joke was quite a standing one because it vexed poor Jack & many were the popular songs parodied which were dinned in his ear. Thomson Hankey was seldom with us, but Frederick always aforemost in teazing his brother Jack, who was of an irritable temper and very easily teazed.

‘You probably know afterwards how the Bedford Square table became always open to Sir Frederick & how Charlotte persuaded him to leave off making sugar, & take a commission in the Guards, which he did before he was of age & before his uncle Tom died. You know how ultimately Charlotte became Mrs F. Hankey & Emma was born, the poor fellow got out of all possible means to support himself & got out to India. Mrs Hankey of Bedford Square was twenty times a mother to the Frederick Hankeys & it is not very likely that Frederick would tell his daughter Emma the anecdotes I have written and therefore I dare say Emma knows nothing of it. I believe Tom Hankey the brother of Barnard must know it, & when Barnard was a boy at Eton School, he once asked my father ‘Uncle, were my father & mother ever married?’ - my father said ‘To be sure they were or how could you be heir to Fetcham?’.

‘As you have happily always lived in an atmosphere of holy walk you can form a very imperfect idea of the sort of way young people spent their time when together, nothing was so constant as quizzing & telling exaggerated good stories of their acquaintance who were considered quizzible, & the Bedford Square people were never forgotten. And Sir Frederick Hankey, who was what is called a very sharp tag, was inexhaustible in his anecdotes. I have often thought that when these things came back to his mind, how he ought to feel ashamed at being afterwards so obliged as he has been to poor Mrs H. whom he used so unmercifully to quiz. My poor Uncle was certainly much fairer game, if any game was considered fair, which it cannot be, for he, with very good sense & good education, chose to lay himself open to the young people to quiz. He had ways of his own which he would not change for the King himself.

‘I also very well remember a grand dinner given by [2nd] Lord & Lady Palmerston in Hanover Square [where they lived] upon the christening of their second son William [in 1788]. Old Aunt Temple [Jane nee Barnard 1715-1789] the Grandmother of the child was alive & stood Godmother for the boy. Uncle Tom was one of the Godfathers & his wife & my father & mother & myself were there. This proved that the marriage was fully acknowledged. It was the most expensive & altogether the finest dinner I was ever at, either before or since & made a deep impression on my young ambitious heart. There was a brilliant assemblage of nobility in the evening - I think these things must convince you there was never a doubt of the legality of the younger branches.

‘The eldest daughter Charlotte very soon became an accomplished & elegant girl, tho’ at first she was under every disadvantage. She was remarkably fond of my mother, who won her heart by once telling her that she herself was married at fifteen & a month (which was the case). ‘O dear Aunt’ said she ‘tell me all about it. I do do love to hear of weddings, Mama will never tell me anything how she was married, which is so ill natured’. ‘O my dear, it is so long ago that I have quite forgot’ said her Mama. These sort of things were continuously occurring & Frederick Hankey laughing ready to kill himself, for as I said he was always at the house - you know they got married one morning at Fetcham Church.

‘The second girl who married Sir Hugh Massy was much more reserved & never took a prominent part in any conversation.

‘Do you think Sir Frederick never told his wife any of these things? But if he did, when he went to India Emma could not have been three years old, & Frederica was born when her mother was so near her end that I was told she never knew she had given birth to another child - but kind Mrs Hankey brought it up with great care’

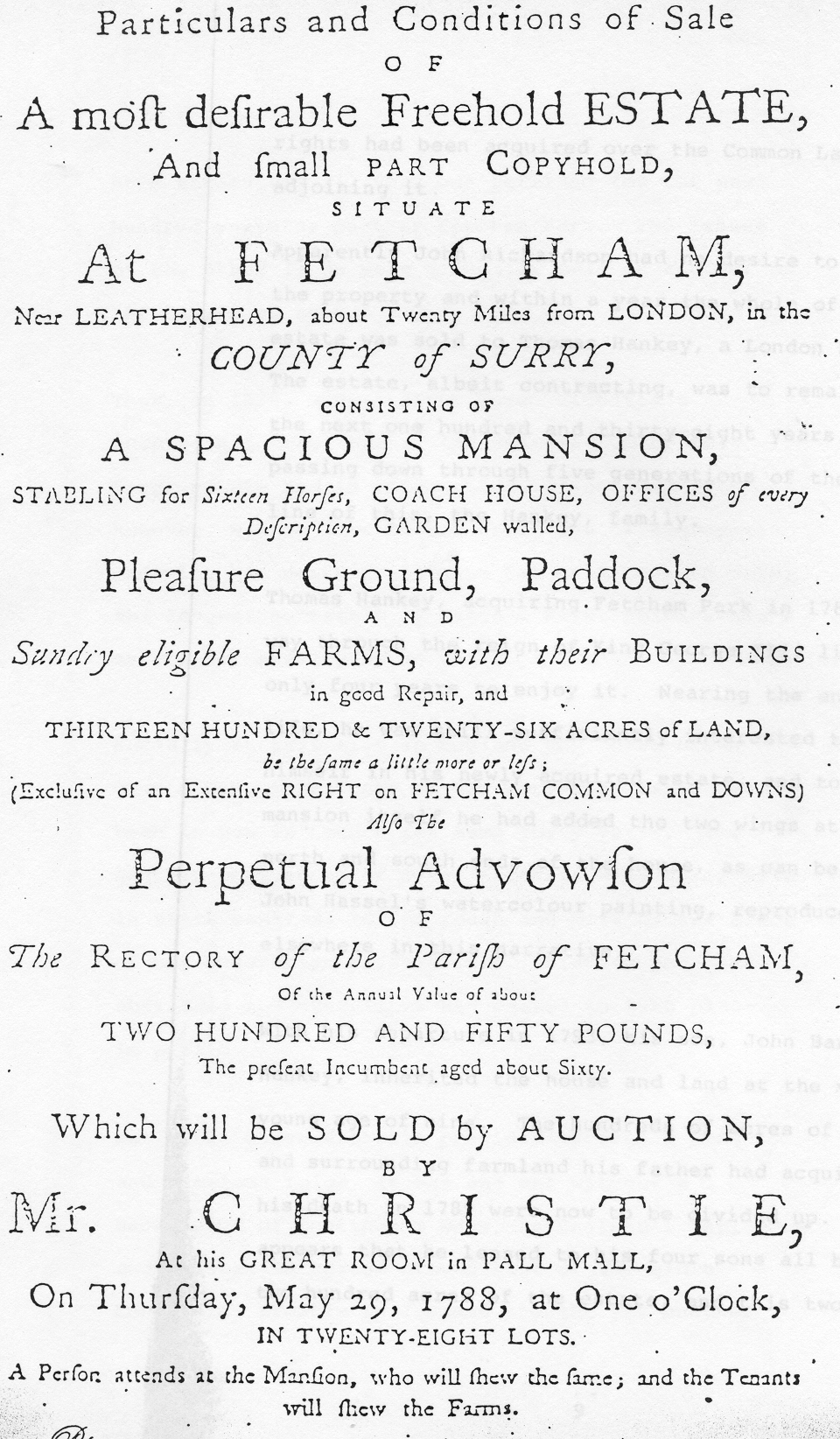

Thomas must also have felt the need for a larger country estate to accommodate his growing family, and to reflect his considerable wealth and position. An estate at Fetcham, near Leatherhead, comprising a mansion, grounds and several farms totalling 1,326 acres had been sold at auction by Mr Christie on 29 May 1788 to Mr John Richardson, for 29,310 guineas. It was the whole of this property, known as Fetcham Park, that Thomas Hankey purchased in the following year, 1789, and he immediately set about improving the mansion by adding two single storey wings.

Thomas Hankey was a strong Pittite and had rendered services to the government, probably in the raising of loans. He was always in hopes to be made a baronet, and in 1790 this appeared near fulfilment when it was reported that Mr Hankey, the Banker, was shortly to be created a baronet.

Extract from Wikipedia:

The mansion was commissioned by Henry Vincent, who inherited the estate from his father in 1697. He chose William Talman, an established architect with a reputation for his mercurial temperament, who was a pupil of Sir Christopher Wren and was in the service of King William III at Hampton Court. Before construction was complete, Vincent moved to Norfolk and let Fetcham Park House to Arthur Moore MP.

Fetcham Park House was sold to Moore for £8,250 in 1705. He invested a fortune on the house and grounds, commissioning the stairway murals and ceiling paintings by the celebrated French artist Louis Laguerre, whose work can also be seen at Blenheim Palace and Hampton Court. It was then too that Capability Brown advised on the garden design. Laguerre was born in Paris in 1663 and came to England in 1684. His father had been in charge of the royal menagerie and Louis XIV was his godfather. As well as Fetcham Park House and Chatsworth, he worked at Burghley, Blenheim, Marlborough House, Hampton Court and Buckingham House.[2]

But Moore spent so extravagantly that after his death in 1730 there were insufficient funds to maintain the estate and it was sold in 1737 to Thomas Revell, Agent Victualler at Gibraltar. Revells descendants sold the estate, then totalling 1,326 acres (5.37 km2), to John Richardson in 1788.

It was soon re-sold to the London banker Thomas Hankey, whose family owned it for the next 138 years. Before his death in 1793 Thomas Hankey added two curved wings at the north and south ends of the house. By 1875 John Hankey inherited the property and commissioned a major refurbishment by the respected architect Edward I'Anson. This was designed to alter the appearance of the house and brought French and Flemish influences to the original Queen Anne design and the later Georgian additions. IAnsons legacy includes the mansard roof and typical Flemish turreted tower block on the west side, providing an entrance hall and two rooms above, and a two storey wing at the south end of the house.

Captain George Hankey was the last of the family to live in the house, dying there in October 1924. Many members of the Hankey family are buried in the graveyard adjoining Fetcham Park.

Said to be Fetcham Park before remodelling, c.1875

(but unlikely)

The Ship Hankey

1774: The ship Hankey, which Captain William Macintosh was taking to the West Indies, was one of eight vessels reported destroyed in a storm at Madeira in 1774; she had on board £14,000 for the use of the troops and Men of War in the West Indies.

1778: The ship Hankey was mentioned in a court case concerning marine insurance

- Simond and another v Boydell:

‘An action was brought against an underwriter, for return of premium. The material part of the policy was in these words: ‘At and from any port or ports from Grenada to London, on any ship or ships that shall sail on or between the first of May and the first of August, 1778, at 18 guineas per cent. to return 8 per cent. if she sails from any of the West India islands, with convoy for the voyage, and arrives.’ At the bottom there was a written declaration that the policy was on sugars (the muscovado, valued at 20l. per hogshead). The ship, the Hankey, sailed with convoy, within the time limited: she arrived in the Downs, where the convoy left her; convoy never coming farther, and indeed, seldom beyond Portsmouth. After she had parted with the convoy, she struck on a bank, called the Pan-Sand, at Margate, and eleven of fifty-one casks of sugar were washed overboard, and the rest damaged. The ship was afterwards got off the bank, and proceeded up the river, arrived safe in the port of London, and was reported at the custom-house. The sugars saved, being sold, produced 340l. instead of 800l., which was a valuation in the policy’

1784: The ship Hankey (not known whether or not the same vessel), 261 tons, had been recorded in Dublin in 1784. She was probably owned by Simond & Hankey, West India merchants and ship owners. She was well suited to the carrying of passengers, having a height of six feet between decks, and was probably involved in what was known as triangular trade, typically transporting sugar, molasses and rum from the West Indies to Britain or the colonies of British North America, and returning with raw resources such as fish, lumber and fur, or various commodities from Great Britain. Other vessels were engaged in a similar trade involving West Africa and the transportation of slaves, but there is no evidence that the Hankey was involved in this. The Hankey, Captain Cheap, sailed from Dublin with 240 passengers and servants, arriving at Philadelphia some two months later on 2 Jun 1784.

1786: The Ship Hankey, Captain Christopher Sundius (again possibly the same vessel) was registered at the Port of London on 7 Nov 1786 and later recorded as Lost.

But in 1792 and 1793 an event occurred which could just possibly have been responsible for the early death of Thomas Hankey:

1792: ‘The Hankey set out on a virtually unknown voyage of death and disease that transformed the four continents that comprise the Atlantic World. The journey of this single ship, which carried yellow fever from West Africa to the West Indies, inadvertently instigated an epidemiological tragedy which, in turn transformed North America, Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean islands.’

The Hankey sailed from Gravesend on 4 Apr 1792 and from Portsmouth later that month, and began a two-month voyage to West Africa, where 275 white British passengers hoped to establish an anti-slavery colony. By demonstrating that black people could work effectively as free rather than bound labourers, the colonists hoped to convince their own nation that Africans could be ‘civilized’. Converting the ship to living quarters, the colonists lived and mostly died, primarily from tropical diseases, off the coast of Africa for the next six months. In desperation, two dozen pioneers tried to sail the Hankey home. The ship limped to the Cape Verde Islands, then caught the trade winds to the West Indies, where she arrived on 19th February 1793. Infected passengers and mosquitoes then spread the ‘black vomit’ (as yellow fever earned its nickname after one of its hideous symptoms). Meanwhile, a violent revolution broke out in the Caribbean as slaves fought to free themselves. When thousands of British and, subsequently, French troops arrived to quell the rebellion, they died like flies, killed by mosquitoes. While the Hankey was still in the West Indies searching for wary sailors to sail on a death ship, commercial and refugee vessels transported passengers escaping the slave revolution along with yellow-fever-carrying mosquitoes to Philadelphia.

The Governor of Grenada, Ninian Home, had reported on 16 Jul 1793 on a malignant fever in St. George’s. He stated ‘from the circumstances which have come to my knowledge, there can be no doubt that this disorder was introduced here by the ship Hankey, Captain Cox, which carried out settlers to the Island of Bulam [on the coast of Guinea], and came to Grenada on her return’. The theory that the disease was carried from Africa to America by the Hankey had been propounded by Colin Chisholm, surgeon to the Ordnance in Grenada.

As the Hankey approached the Downs at the end of her return voyage to England in the summer of 1793, she had the mate and a number of hands (all of whom subsequently died) pressed out of her, notwithstanding that the captain warned the press-gang of the dangerous consequences which might ensue. The Privy Council issued an order to sink the vessel, along with its cargo and its passengers, if necessary, to put an end to its tour of death and devastation. The Hankey escaped that fate, but upon reaching the Thames, the ship dropped anchor on 2 Oct 1793 and was quarantined at Stangate Creek. On 6 Aug 1793, The Times reported that ‘A very dangerous distemper has for some time raged on board the ship Hankey, now performing quarantine. It is thought she will be ordered to be burnt.’ This almost cetainly occurred, and the ship was burned to the water line, together with her cargo of cotton and possibly silk. On the other hand there is a report that the ship Hankey, Captain Kirby, sailing to London, sank in Port Antonio, Jamaica in 1795 (the crew and cargo being saved).

It could be more than a coincidence that Thomas Hankey’s friend and lawyer Samuel Troughton of Hoxton Square and Stratford died on 31 July 1793, perhaps after inspecting the ship. Thomas Hankey’s younger brother John Hankey, senior partner of Simond & Hankey, had died on 29 Aug 1792, aged 51, but his death can hardly have been related to the final voyage of the Hankey.

Thomas Hankey was interested in maritime matters and may have had a financial interest in the Hankey, so it would not be surprising if he too, in the absence of his brother John, had inspected her on her arrival in London. In any event, Thomas died not long afterwards on 13 Sep 1793 at Bedford Square, aged only 53, having lived only four years to enjoy his new estate at Fetcham. He was buried on 21 Sep in the family vault at St Dionis Backchurch.

Thomas Hankey had by his own hand made his will on 1 Aug 1788, and a codicil on 5 Feb 1791, following the birth of his second son Thomas at Fetcham. The executors were his wife Elizabeth, his son William Alers and William Duncan. Not having been drawn up by his lawyer (Charles Druce of Fenchurch Street) the will was partially defective, and Thomas died intestate as to his freehold and leasehold estates, and his eldest son John Barnard Hankey became his heir at law. In 1794 his trustees applied to the court of Chancery for directions as to proper administration of the estate, and estimated the lands in Surrey, London and Middlesex to have a yearly value of £1500 and upwards, the lands at Fetcham £300 and Murcoat Farm, Wiltshire, held for lives, £115; the residue of personal estate and effects (presumably after the specific legacies totalling £100,000) was estimated at £100,000 and upwards.

His widow Elizabeth died on 5 Apr 1829 at Bedford Square, aged 78, and was buried on 13 Apr at St Dionis Backchurch.

Thomas Hankey and Elizabeth Hankey were reinterred at Kensal Green Cemetery in July 1878 (catacomb B, vault 45), consequent on the demolition of St Dionis Backchurch.

Arms: Quarterly I and IV per pale gules and azure, a wolf rampant erminois vulned on the shoulder of the second, II and III argent a bear rampant, sable, muzzled or, Barnard impaled the same

Chronological Summary

1740 Born [Clapham]; baptised City

1765 Partner of Hankey & Co.

1770 His father, Sir Thomas Hankey, died

1771 Son William Alers born, London (where?)

1773 Known to be at Southborough, Bromley, Kent

1773 Head partner of Hankey & Co.

1774 Dau. Charlotte Weaver/Hankey born, baptised Westminster

1776 Dau. Sarah Hankey born, baptised Bromley

1779 Dau. Louisa Hankey born, baptised Bromley

1781 Married Elizabeth Weaver, St Martin in the Fields

1784 Son John Barnard Hankey born at [Fenchurch St] baptised City

1784 Inherited the estate of John Barnard, his uncle

1786 Dau. Elizabeth Hankey born, baptised City

1786 Known to be still at Southborough, Bromley

1786 Bought lease of 18 Bedford Square

1788 Son William Alers at Edinburgh University

1789 Purchased Fetcham Park

1791 Son Thomas Hankey born at Fetcham

1793 Died at Bedford Square; buried City